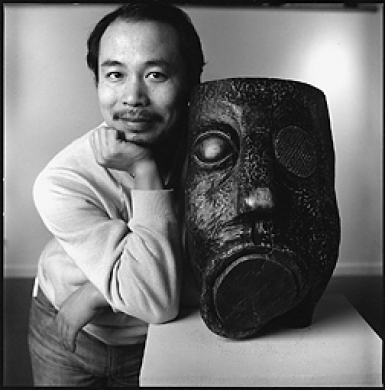

Born in Beijing in 1949 (the year of the establishment of the People's Republic of China) and raised by a family accomplished in art — his mother is an actress and his father is a writer, Wang Keping is one of the key figures in the most historic art movement in the history of contemporary China.

His youth is marked by the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Enlisted in the army and dispatched into the mountains and rural areas, he first worked in a factory and then turned to novel a... nd play writing. During the time of Red Guard Movement of Cultural Revolution, he survived from the reeducation and gradually found his talent in art.

It was in the domain of sculpture that Wang Keping finds his own path of artistic independence.

As an autodidact, He begins from wood carving with a dream always born in mind -- to work someday on bronze, the material used by the sculpture masters. He created his first work “Long Live Chairman Mao” (1978) with a simple piece of reclaimed wood, rarely seen in that age, this piece represents a polemical image through a huge desperate face, firmly grasping the “Little Red Book” in a raised hand.

In 1979, taking advantage of the Post-Cultural Revolution or “Spring of Beijing”, Wang Keping, along with Ai Weiwei, founded an unofficial anti-conformist artist group named “Xing Xing” (The Stars), notable names among the members including Huang Rui, Ma Desheng and Zhong Acheng. “We had chosen this name – The Stars,” recalled Wang Keping, “because we were the only glimmers who sparkle in the endless night and no matter how tiny they seem from afar, they turn out to be gigantic planets.”

Idol and Silence, the two works he exhibited, aroused much controversy, which later had a large repercussion in the history of Chinese contemporary sculpture — the censorship has getting stricter ever since.

In 1984, he moved to Paris, the homeland of great sculptors, in search for liberty. There, he discovered different wood species and allowed himself to be guided and inspired by the natural forms of the material.

Wang Keping found the possibility of unique expressions in the material. The artist spent as much effort in selecting the suitable wood species and forms as in sculpting: knots and excrescences are thus transformed into animated bodies through the strong inspiration enlightened by this living material.

The combination of the proper simplicity of drawing by the calligraphic gesture and the black patina obtained by the fire (the top layer of the wood burned by the blowtorch hardens more or less according to its density) marks its allusive figures by a radical imprint. “I'm going towards what reveals the manifestation of a presence", he said, willingly laconic. Figures that combine characters of Chinese culture, sensuality and sometimes, even eroticism, reveal “an instinctive feeling of sculptural forms sometimes going as far as burst”.

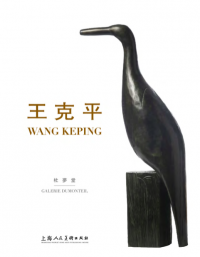

Marked by a deep search in the essential, his work exalts the female body with his stylized sculptures of voluptuous women but also the animal kingdom with the series of Birds and of Dogs.

Through these topics, he seeks to reach the vital essence of both human and animal forms. Engaged in a sensual and organic interpretation, he prefers the form of abstract figuration, of which the plans are simplified, only the material remains as the origin of the existence of his works.

In the early 1990s, Wang Keping finally began to explore bronze. He chose some of his works and made some modifications to present the eternal beauty of this material — resistant to the passing time with the testimony of the ancient Chinese bronzes that are still preserved today. He redid and reinterpreted the forms in wax and the patina to create a unique rendering, with the boundaries between stone, wood and metal, the sculptor thus becomes the creator.

The bronze then transcends the artist’s sculptures and makes them more remarkable; it gives his work a special place among the collectors and in the largest museums among the bronze works by Rodin, Bourdelle, Moore and many others.

Numerous exhibitions have been dedicated to Wang Keping all over the world and his artistic signature remains unique and emblematic today as a symbol of the birth of Chinese contemporary art.

READ MORE

His youth is marked by the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Enlisted in the army and dispatched into the mountains and rural areas, he first worked in a factory and then turned to novel a... nd play writing. During the time of Red Guard Movement of Cultural Revolution, he survived from the reeducation and gradually found his talent in art.

It was in the domain of sculpture that Wang Keping finds his own path of artistic independence.

As an autodidact, He begins from wood carving with a dream always born in mind -- to work someday on bronze, the material used by the sculpture masters. He created his first work “Long Live Chairman Mao” (1978) with a simple piece of reclaimed wood, rarely seen in that age, this piece represents a polemical image through a huge desperate face, firmly grasping the “Little Red Book” in a raised hand.

In 1979, taking advantage of the Post-Cultural Revolution or “Spring of Beijing”, Wang Keping, along with Ai Weiwei, founded an unofficial anti-conformist artist group named “Xing Xing” (The Stars), notable names among the members including Huang Rui, Ma Desheng and Zhong Acheng. “We had chosen this name – The Stars,” recalled Wang Keping, “because we were the only glimmers who sparkle in the endless night and no matter how tiny they seem from afar, they turn out to be gigantic planets.”

Idol and Silence, the two works he exhibited, aroused much controversy, which later had a large repercussion in the history of Chinese contemporary sculpture — the censorship has getting stricter ever since.

In 1984, he moved to Paris, the homeland of great sculptors, in search for liberty. There, he discovered different wood species and allowed himself to be guided and inspired by the natural forms of the material.

Wang Keping found the possibility of unique expressions in the material. The artist spent as much effort in selecting the suitable wood species and forms as in sculpting: knots and excrescences are thus transformed into animated bodies through the strong inspiration enlightened by this living material.

The combination of the proper simplicity of drawing by the calligraphic gesture and the black patina obtained by the fire (the top layer of the wood burned by the blowtorch hardens more or less according to its density) marks its allusive figures by a radical imprint. “I'm going towards what reveals the manifestation of a presence", he said, willingly laconic. Figures that combine characters of Chinese culture, sensuality and sometimes, even eroticism, reveal “an instinctive feeling of sculptural forms sometimes going as far as burst”.

Marked by a deep search in the essential, his work exalts the female body with his stylized sculptures of voluptuous women but also the animal kingdom with the series of Birds and of Dogs.

Through these topics, he seeks to reach the vital essence of both human and animal forms. Engaged in a sensual and organic interpretation, he prefers the form of abstract figuration, of which the plans are simplified, only the material remains as the origin of the existence of his works.

In the early 1990s, Wang Keping finally began to explore bronze. He chose some of his works and made some modifications to present the eternal beauty of this material — resistant to the passing time with the testimony of the ancient Chinese bronzes that are still preserved today. He redid and reinterpreted the forms in wax and the patina to create a unique rendering, with the boundaries between stone, wood and metal, the sculptor thus becomes the creator.

The bronze then transcends the artist’s sculptures and makes them more remarkable; it gives his work a special place among the collectors and in the largest museums among the bronze works by Rodin, Bourdelle, Moore and many others.

Numerous exhibitions have been dedicated to Wang Keping all over the world and his artistic signature remains unique and emblematic today as a symbol of the birth of Chinese contemporary art.

READ MORE